CARBOGEM | Bachelorarbeit 2024

Das Anthropozän hat zu einem weltweiten Rückgang der ozeanischen Ökosysteme geführt, wobei Riffe zu den empfindlichsten gehören. In den gemäßigten Zonen sind Austern die Schlüsselarten, die diese Biodiversitätshotspots bilden. Leider leiden die Riffe stark unter menschlichen Aktivitäten wie Verschmutzung, Überfischung, steigenden Temperaturen und der Versauerung der Ozeane. 85 Prozent der weltweiten Austernriffe sind bereits abgestorben.

Nicht nur die Meeresbewohner, sondern auch die Küstengemeinden sind von der Vitalität der Austernriffe abhängig, da sie wichtige Ökosystemleistungen wie Wasserfilterung und Küstenschutz vor Überschwemmungen und Erosion erbringen.

Viele Initiativen versuchen daher, diese Ökosysteme mithilfe von künstlichen Riffen wiederherzustellen. Dabei wird eine Vielzahl von Materialien und Designs getestet, die meist aus Beton bestehen. Die gängigen Materialien können jedoch ökologisch problematisch sein, da sie nicht erneuerbar sind oder bei der Herstellung CO2 freisetzen und damit teilweise selbst zu dem Problem beitragen.

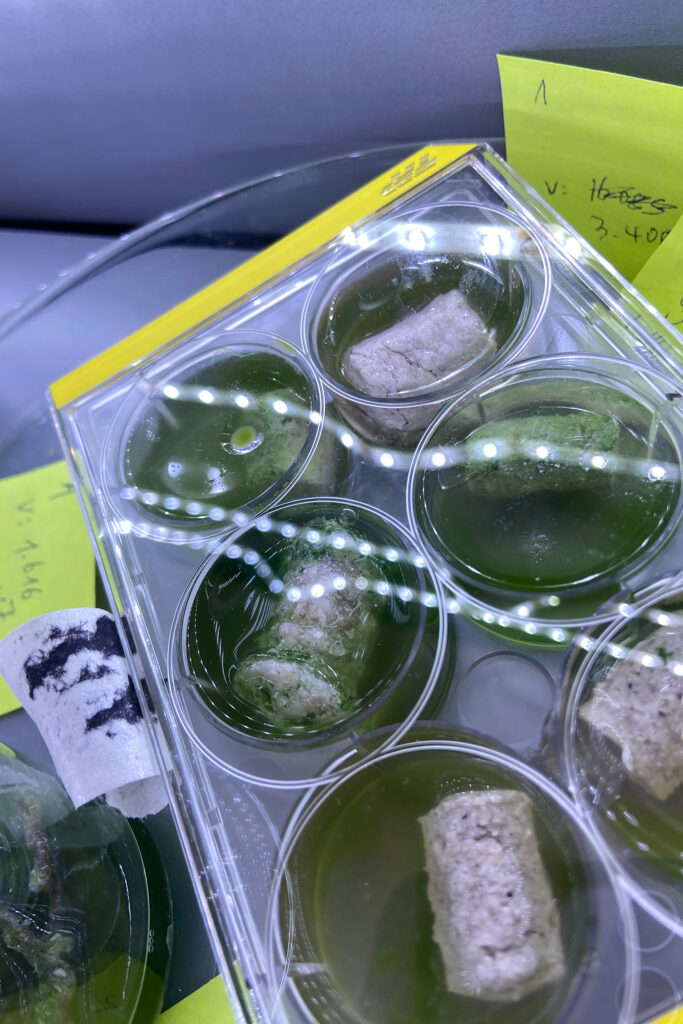

CARBOGEM ist ein künstliches Riffmodul, das aus einem neuartigen Beton besteht, welcher in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Fraunhofer Institut entwickelt wurde. Das Material basiert auf erneuerbaren Rohstoffen, mit recycelten Austernschalen als Hauptbestandteil. Anstelle von herkömmlichem Zement zur Bindung des Austernaggregats wird die Biozementierung durch photosynthetische Cyanobakterien genutzt. Dieser Prozess kann atmosphärisches CO2 binden und die Module in Kohlenstoffsenken verwandeln.

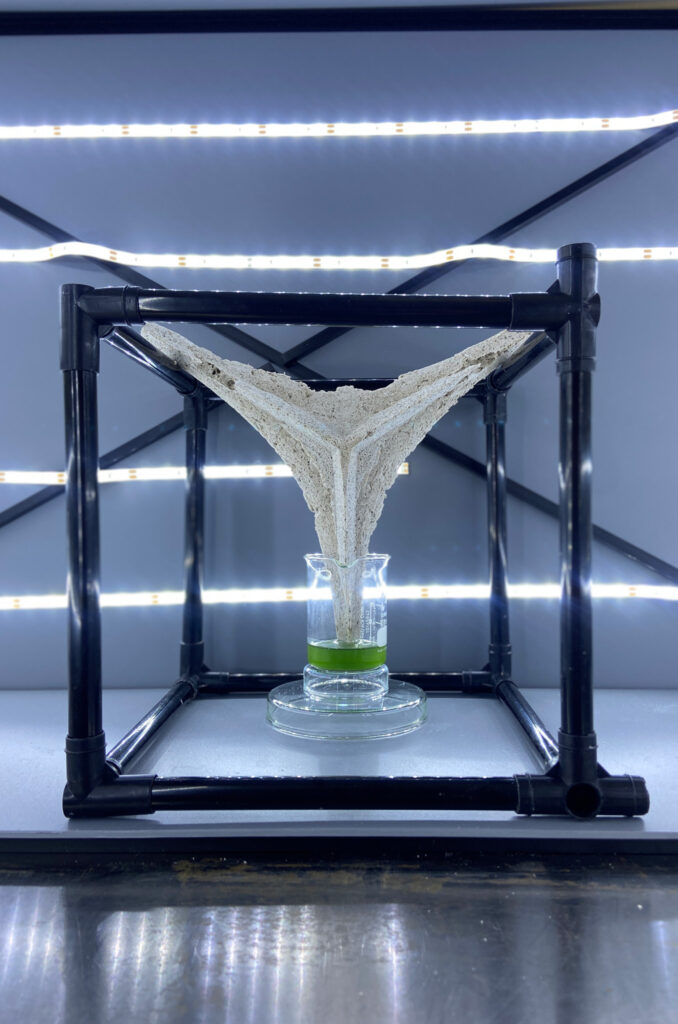

Die CARBOGEM Module sind so konzipiert, dass sie für Meeresorganismen biorezeptiv sind und das Wachstum eines gesunden Riffökosystems initiieren. Von der Materialzusammensetzung, Porosität und Oberflächenstruktur, die Austernlarven anzieht, bis hin zur Topologie, die Lebensraum für eine Vielzahl lokaler Riffflora und -fauna bietet.

Die Module haben eine Größe von 25x25x10 cm und lassen sich leicht mit dem Boot transportieren und von Tauchern in der gewünschten Struktur ausbringen. Zu Monitoring-Zwecken können einzelne Module an die Oberfläche gebracht und auf ihre Besiedlung untersucht werden.

Die Formen der Module sind so konzipiert, dass sie sich selbstassemblierten und zu starren Strukturen mit vergrößerter Oberfläche werden, damit sich die Austern schnell festsetzen und anschließend ein Riff bilden können. In diesem Fall wird die gesamte Struktur überwachsen und in ein Riff integriert. Doch schon vor der Besiedlung wirken die Strukturen selbst als Küstenschutz, indem sie die Wellenenergie ableiten, Erosion verhindern und so die Küsten vor dem Anstieg des Meeresspiegels und vor Überschwemmungen schützen.

Die Anordnung der Strukturen kann individuell an die örtlichen Gegebenheiten, wie unebene Meeresböden, Küstenlinien und spezifische Restaurierungsziele, angepasst werden. So können die Module beispielsweise zur Überbrückung bestehender Riffe eingesetzt werden und Schutzkorridore bilden, durch die Meeresbewohner migrieren und neue Lebensräume besiedeln können. Eine weitere Möglichkeit ist die Initiierung eines neuen Riffs in einem geeigneten Gebiet oder die Sicherung von instabilem Substrat, das durch Schiffe beschädigt wurde.

Bei ungeeigneten Bedingungen und fehlender Besiedlung durch Austern können die Module entweder vollständig wiederverwendet und an anderer Stelle aufgebaut werden oder auf unbestimmte Zeit auf dem Meeresboden verbleiben, da sie zu 100 % biobasiert, ungiftig und sogar in der Lage sind, den enthaltenen Kohlenstoff zu binden, wodurch sie als langfristige Kohlenstoffsenken fungieren.

Turning carbon into gems.

The Anthropocene has caused a global decline in oceanic ecosystems, with reefs being amongst the most sensitive. In temperate zones, oysters are the keystone species that create these biodiversity hotspots. Sadly, reefs are declining globally due to human activities such as pollution, overfishing, rising temperatures, and ocean acidification. 85 percent of the world’s oyster reefs have already died off.

Not only marine life, but also coastal communities depend on the vitality of oyster reefs, as they provide essential ecosystem services like water filtration and coastal protection from floods and erosion.

Many initiatives are therefore attempting to restore these ecosystems with the help of artificial reefs. A variety of materials and designs are being tested, mostly made from concrete. However, the common material choices can be environmentally problematic as they are non-renewable or release CO2 during production, partially contributing to the problem themselves.

CARBOGEM is an artificial reef module made from a novel concrete developed in collaboration with Fraunhofer Institute. The material is based on renewable resources, with recycled oyster shell waste as the main component. Instead of using common cement for binding the oyster aggregate, it aims to use biocementation conducted by photosynthetic cyanobacteria. This approach can fix atmospheric CO2, converting the modules into carbon sinks.

The CARBOGEM modules are designed to be bioreceptive to marine organisms and initiate the growth of a healthy reef ecosystem. From the material composition, porosity and surface structure that attracts oyster larvae, to the topology that provides habitat for a variety of local reef flora and fauna.

The modules have dimensions of 25x25x10cm, making them easy to transport by boat and deploy by divers into the desired structure, eliminating the need for heavy-duty machinery. For monitoring purposes, single modules can be resurfaced and analyzed for colonization.

The modules‘ shapes are designed to self-assemble and interlock into rigid structures with increased surface area for quick oyster attachment and subsequent reef formation. In this case, the whole structure will be overgrown and absorbed into a reef. Nevertheless, even before colonization, the structures themselves act as coastal protection by dissipating wave energy, preventing erosion, and thereby protecting the coastlines from sea-level rise and floods.

The layout of the structures can be individually adapted to local conditions, such as undulating sea floors, coastlines, and specific restoration goals. For example, the modules can be used to bridge existing reefs and form protective corridors for marine life to migrate and populate new habitats. Another option is the initiation of a new reef in a suitable area or the securing of unstable substrate that has been damaged by ships.

In the case of unsuitable conditions, and absent colonization by oysters, the modules can either be entirely reused, reassembled elsewhere, or remain on the seafloor indefinitely, as they are 100% bio-based, non-toxic, and capable of locking away the contained carbon, acting as a long-term carbon sink. Turning carbon into gems.

Prüfer

S. Alkalay, H. Neumann, M. Ahlhelm

Prozess